PERCEPTION OF PUBERTY IN THE TIME OF SHAKESPEARE – THEATRE AS A MIRROR ON THE WORLD IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

A live conversation by George Werther in Athens, September 2018

With contributions by Ze’ev Hochberg and Alan Rogol

The subject of puberty or adolescence in the 17th century is fascinating. Where better to go than to the Bard (William Shakespeare), who had a lot to say about puberty in a variety of his works. Perhaps the most germane quote is this one, from “A Winter’s Tale”, spoken by the Old Shepherd:

I would there were no age between ten and

three-and-twenty, or that youth would sleep out the

rest; for there is nothing in the between but getting

wenches with child, wronging the ancientry, stealing,

fighting- Hark you now! Would any but these boiled brains

of nineteen and two-and-twenty hunt this weather?

-William Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale, 3.3.58–64

Translation: I wish children could jump from age 10 to 23 (avoiding puberty). During this period they indulge in rampant sexual activity, making young girls pregnant, they abuse their elders, they steal, they fight. By age 19-22 their brains have been addled!

In this short speech, we see an eloquent summary of the “adverse” social impact of puberty, including rampant sexual activity resulting in unwanted pregnancy, disrespect for elders, violence, theft. The Old shepherd attributes this to “boiled brains”. He suggests it would be best to skip ages 10 to 23 (!!).

On the other hand, adolescence as an idyllic time from the point of view of the individual, especially in retrospect, is also referenced in Winter’s Tale when Hermione asks Polixenes about his early relationship with her husband.

He replies:

We were, fair queen

Two lads that thought there was no more behind

But such a day tomorrow as today

And to be boy eternal

We were as twinned lambs that did frisk in the sun

And bleat the one at the other: what we changed

Was innocence for innocence; we know not

The doctrine of ill-doing, nor dreame

That any did

Translation: As youth, we lived for the moment, and believed that we would be ever-young (Peter Pan-like). We were innocent with no malice, and thought ill of no-one. In other words as adolescents they lived idyllic and very happy lives. Their perspective was at complete odds to their elders.

Shakespeare was of course a master of insight into the human condition, such that in Winter’s Tale he provides the dual perspective of the trials of adolescence from the parent or elder perspective, while also getting inside the head of the hedonistic adolescent boy.

These observations and others are very well discussed in a recent publication by Victoria Sparey: Performing Puberty: Fertile Complexions in Shakespeare’s Plays https://muse.jhu.edu/article/592004>. Shakespeare Bulletin, Volume 33, Number 3, Fall 2015<https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/32417, pp. 441-467. She describes many references to puberty in Shakespeare’s plays, also including Romeo and Juliet (of course), Twelfth Night, Merchant of Venice, As You Like It, Henry IV Part 1, Measure for Measure, and Much Ado About Nothing. A recurring theme is the effect of puberty on various characters, which must be seen in the context of contemporary perceptions of the mechanisms in involved, and the effects of puberty on both body and behaviour.

THE LIFE CYCLE IN THE TIME OF SHAKESPEARE

In brief, the life cycle, in Shakespeare’s time, was seen as involving processes of heating and cooling, so that youth were hot and dry, where adolescents became dissociated from the excessive moisture of childhood (Cuffe, 1607), but still possessed the surplus heat that promoted such heat-fuelled acts as violence and argument. With increasing age, Cuffe writes that “cooling’ then occurs : An age is a period and tearmes of mans life, wherein his natural complexion and temperature naturally and of its owne accord is evidently changed”. Francis Bacon (1638) added, quite insightfully: The Ladder of Mans Bodie, is this [. . .]. To bee Borne; To Sucke; To be Weaned; To Feed upon Pap; To Put forth Teeth, the First time about the Second yeare of Age; To Begin to goe; To Begin to speaks; To Put forth Teeth, the Second time, about seven years of Age; To come to Pubertie, about twelve, or fourteene yeares of Age; To be Able for Generation, and the Flowing of the Menstrua; To have Haires about the Legges, and Armeholes; To Put forth a Beard; And thus long, and sometimes later, to Growing Stature; To come to full years of Strength and Agility.

Translation: The sequence of development in man is birth, suckling, early eating of soft mush, dental development, walking in the second year, then speaking, secondary dentition from seven years, puberty from 12-14 years, with reproductive ability, menstruation, pubic and axillary hair, facial hair, linear growth, to final adult height and muscularity.

This of course was based on the seven-year stages of man’s life cycle first described by Pythagoras and Hippocrates in Ancient Greece.

HUMORAL THEORY

Interestingly, in this period, namely around 1620, the concept of adolescence was rather vague, but there were certainly theories at that time about the mechanisms of puberty. These theories, as for general thoughts about the ages of man, related to “humors” or bodily fluids, both their abundance and their heat content. – such that each stage of the life cycle was thought to be closely related to the state of the body’s humors. Ageing was thought to represent a process of cooling and drying out.

The humoral theory said that the male is hot and dry and the female is cold and moist. Hippocrates in fact described women as “cold men”. Shakespeare adhered to Hippocrates’ four humor theories. The adolescent male (who we will discuss further as a key Shakespearean actor) is somewhere between these two points, being somewhere between the hot male and the cool female.

A woman’s moister and cooler body was related to menstruation (which removes the “heat”). Menstruation was then the critical event which differentiated men and women.

Bodily changes were discussed in ripening and fruitful terms. In 1592 Lemnius warned against men marrying too soon as “ere they be fully rype. – they lack manly strength and theyre seed is cold and thin”. So that the heat of puberty precipitated the ripening of the seed via generative heat. As adolescence proceeded and “budding and blossoming” occurred, a requisite was that both male and female bodies became “hotter”, so that they could eventually participate in sexual intercourse. This is in contrast of course with the male/female hot/cold model and the fact that this event begins in adolescence sets the male/female differences apart from that time.

Thus, while most changes were gender-specific, some were not, including sexual desire, which was thought to be a manifestation of humoral excess in a body no longer requiring heat and moisture for body growth. – this “heat to spare” was said by Aristotle to influence the mind to sexual activity. Interestingly, it was also thought that humidity arising from the seed of the male, subject to greater heat than in the female, would rise higher in the body to alter vocal chords, while humidity in the female was associated with swelling breasts. So testosterone/oestrogen were in a sense recognised.

BODY HAIR

Body hair was paid much attention and given much significance: Aristotle said Hairinesse is a sign of abundance of a man’s generative strength (again testosterone). Will Greenwood noted this in 1657 – lack of a beard was associated with men who were commonly cold and impotent. Beards were thus also a matter of much discussion, as a sign of sexual maturation. In Henry IV Part 1, Falstaff challenges Hal’s manliness “whose chin is not fledged” by stressing that the beardless youth will remain so: “I will sooner have a beard in the palm of my hand than he shall get one on his cheek”. …”a barber will never earn sixpence from the prince” In other words, Falstaff is challenging Hal’s manliness by suggesting that he (Falstaff) is more likely to grow hair on his palm than Hal is to grow hair on his chin. He also jests that he will never give a barber business (he will never need a shave).

Beards and other signs of puberty were then often used by Shakespeare and others in many plays, examples of some being listed above. The references were often derogatory regarding lack of masculinity, but sometimes highlighted the social or sexual tensions in various scenarios. So the issue of the beard became a common one in Shakespeare’s hands, be it in humour or insult, or simply in observation or prediction of a man’s biological state. In contrast, Coriolanus is described as already exhibiting masculinity at age 16 when he was beardless …”with his Amazonian Chin he drove”. (Amazons)

In 1607, Henry Cuffe described male puberty “when our cheeks and other more hidden parts begin to be clothed that mossie excrement of hair”. In contrast, early texts explained the lack of body hair in women -:the matter and cause of the hayre of the bodies is expelled in their monthly tearmes…”. In other words, menstruation (while demonstrating generative potential) removed the excess moisture from the body that produced beards in men. The excess heat and moisture in men’s seed rose to his face and produced a beard, while the cooler but still heated humoral excess in women was released via menstruation.

In “As You Like It” an awaited beard is used to assess the adolescent Orlando’s readiness for romantic coupling with Rosalind, who asks: “Is his chin worth a beard?”. Celia responds that he “hath but a little beard“. The anticipation of Orlando’s further masculine development and his “love sickness for Rosalind is then measured by his beard. He “lacks the symptoms of a “beard neglected” The promise of his chin encourages her to await his sexual maturation – she “will stay the growth of his beard”.

This left the issue of pubic hair to be explained. This became a subject of humorous puns; whereby female pubic hair was described as an alternative “beard”. Chaucer played on this in The Miller’s Tale. Of course, female pubic hair was also recognised as a sign of sexual maturity. It was mistakenly thought that humoral excess from the woman’s seed stimulated hair growth around her genitalia AFTER menstruation had begun.

In “Twelfth Night”, when Viola (a girl played by a boy actor) is disguised as Cesario (a boy), discussion centres on “Beards”, both facial and pubic. Feste mocks Cesario’s (actually Viola) lack of a beard, to which “Cesario” responds “I am almost sick for one, though I would not have it grow on my chin”. Does she/he mean reference to Duke Orsino (for whom she is lovesick) or is she referring to pubic beard. Feste believes he is speaking to a male youth awaiting the growth of his beard, but “Cesario” (actually Viola) is likely referring to pubic hair – signifying Viola’s longing for pubertal progression via menarche and subsequent pubic hair growth.

BLUSHING

Blushing was thought to represent an alternative response to excess heat on the face of a woman (rather than the facial hair of a man) -indicating ripeness or fertility – erotic because it was thought to result from excess heat arising from the young woman’s seed – heated passion, Vermillion blush.

In Measure for Measure, Isabella’s virginity is identified by her “cheek-roses”. Rosy cheeks give her sexual “ripeness” – the heated process of her maturation is evidenced by her blushing (which would have been exaggerated by cosmetics on stage). Lucio tells her she is “too cold”. “Be that you are – that is a woman as you are well expressed by external warrants – in other words her blushing tells Lucio that she is a “ripened” woman, and he says she should act that way and not be “cold”. In Winter’s Tale, Perdita has blushing cheeks. The shepherd tells her: “Come quench your blushes and present yourself”. When she interacts with her suitor Florizel, “he tells her something/That makes her blood look on’t.” In other words he makes her blush, presumably via some sexual suggestiveness.

In Much Ado About Nothing, Claudio says, regarding Hero’s blushing face “Behold, how like a maid she blushes”..She knows the heat of a luxurious bed/Her blush is guiltiness” Her blush gives away her sexual awareness or experience.

THE BLANK CANVAS OF THE ANDROGYNOUS EARLY PUBERTAL MALE

Theatre companies thus could stage male or female puberty in young male pubescent bodies via blushing of the womanly cheek, the youthful male’s promising chin, or the emasculating lack of a beard. Women were not actors, possibly because the theatre was not considered a fit place for women. All the actors in Shakespeare’s time of course were male, so that young boys played both boys and girls. In a sense, prepubertal or early pubertal boys were regarded as “ambiguous” or a “blank page” upon which gender was written. This is further confounded by “cross-dressing” heroines in As You Like It and Twelfth Night, where a boy plays a girl who pretends to be a boy! It is suggested that “eroticised boys are a middle term between men and women. Nevertheless, the “boy” actor was regarded as ambiguous or feminine, despite early pubertal changes – with a shift to masculine as the voice breaks.

“Boy actors must fit naturally into the parts of pretty well-bred girls, have waistlines that would suit a stomacher, and sufficient agility and grace to manage the cumbersome skirts of an Elizabethan farthingale. The boy actor must cut a fashionable figure too in doublet, cloak and trunk-hose; girls travestied as boys were always immensely popular with an Elizabethan audience and Shakespeare allowed his comic heroines frequent excuses to put on masculine apparel to give their mentality and speech a slightly ambiguous hermaphroditic cast. With their strange mixture of innocence and experience, romantic feeling and sharpspoken candour, masculine bravado and feminine nervosity, they tread a delicate line between the sexes. None of them is a completely mature woman; they belong to a period of human existence when the mildest girl is sometimes tomboyish and even the most energetic boy may now and then have girlish tears” (Quennell 1964)

This is in some ways reminiscent of current transgender issues in our society!

SOME FAMOUS SHAKESPEAREAN ADOLESCENTS

“Romeo and Juliet” is clearly concerned with many aspects of adolescence and puberty. As you will recall, it deals with the “extremes of adolescent action”, namely passionate infatuation (Juliet was 13 years old!!). It has been described as “rites of passage, phallic violence, and adolescent motherhood – typical for youth in Verona. This was on a background of dealing with patriarchal familial bonds.

Also, Romeo demonstrates the typical adolescent intense crush and fickleness, where his desperation at losing Rosaline is immediately replaced by his equal passion for Juliet: “Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight/for I ne’er saw true beauty till this night.”

Similarly, Juliet, initially a compliant innocent young girl, is transformed by passion as she encounters Romeo – her loyalty and devotion to family are swept away. She becomes devious and lies to her parents and defies her father…sounds familiar? Worse still, the loss of her lover Romeo drives her to a self-destructive act – again familiar in modern times. The consequent fantasy that adolescent suicide will make the parents so remorseful that they will mend their ways is realised in the case of the Montagues and the Capulets, who erect statues in their memory and end their blood feud.

Miranda, Prospero’s daughter in “The Tempest” is in contrast to Juliet, whose adolescent passion and ardour is released and her lust is not curbed. On the other hand, Miranda is different: When Prospero finds Ferdinand and Miranda in his cave playing chess (!!!) – reflecting their infantile narcissism, Prospero tells Ferdinand; “If thou dost break her virgin knot before all sanctimonious ceremonies may with full and holy rite be administered, barren hate, sour-eyed disdain and discord shall betrew the union of your bed with weeds so loathly that you shall hate it both”.. they obey (perhaps unsurprisingly after such a dire warning by her father)- and curb their lusts, which were then confined to the chessboard.

PARENTS AND PUBERTY IN EARLY THEATRE – GREENSICKNESS

Much has been written about the girl entering puberty from the days of the ancient Greeks, but this literature is not widely known. I am indebted to Ursula Potter from the University of Sydney. She publishes on the early modern period and how theatre represents sexuality, puberty, gender etc.

Potter writes in a paper from 2013 {Navigating the Dangers of Female Puberty in Renaissance Drama), focusing on the issue of “Greensickness: and how it was understood and dealt with in Theatre of the time. She sets the scene by quoting from Jane Sharp’s midwifery manual of 1671: The Midwives Book: Or the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered. Sharp warns that once the courses flow at fourteen maids will not be easily ruled…..lustful thoughts draw away their minds and some fall into Consumptions, others rage and grow almost mad with love”. “Consumption” meant “Greensickness”, a popular term until the late 19th century. Many other terms were used, including Chlorosis, Tahiti fever, virgin’s disease, white jaundice, leukohlegmata, and cachexia.

The term “greensickness” referred to sexually green youth. The symptoms included eating disorder, amenorrhoea, fatigue, irrational behaviour, promiscuity or frigidity(!), depression and suicidal tendencies. It was the Forme Fruste of anorexia nervosa! It was mostly seen in well to do girls living an indolent lifestyle, and who usually were forced to delay sexual activity until after marriage. It was considered a condition related to the onset of menarche and the absence of sexual activity. It was attributed to the danger of retained menses or female seed once the girl had reached “ripeness”. The “cure”, as colourfully described by the midwife Jane Sharpe, was “marriage” or more specifically sexual activity “to open the obstructions and make the courses come down”. Several 17th century authors concurred, including the physician Lazare Riviere who wrote: “It is very good Advice in the Beginning of the Disease, before the Patient begins manifestly to rave, or in the space between her fits, when she is pretty well, to marry her to a lusty young man. For so the Womb being satisfied the Patient may per adventure be cured.

Several plays of the era thus suggested that young women needed regular sexual activity in order to remain healthy, while at the same time these plays satirised the likely over-diagnosis of “greensickness”. For example, Johnson in “The Magnetick Lady”(1632), parodies the pandering by physicians to their wealthy clients’ obsession with green sickness. Another of these plays is “The Two Noble Kinsmen” by Shakespeare and Fletcher. The jailer’s 15 year old daughter suffers from many of the symptoms of green sickness, including weeping, loss of appetite, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts – put down to unrequited lust. She says, regarding the prisoner Palamon:

“Let him do

What he will with me, so he use me kindly,

For use me so he shall, or I’ll proclaim him,

And to his face, no man”

In other words, she is desperate for sexual union with this man – if he refuses she will proclaim him to be unmanly. This need for sexual gratification again points to the “cure” for green sickness. She further graphically fantasizes:

“He’ll tickle’t up/ in two hours if his hand be in”.

THE ORIGIN OF “HYSTERIA”

Tickling the uterus was a therapy available to young women suffering from “fits” or other green sickness-like symptoms thought to be related to unrequited sexual urge – if sexual intercourse was not an option (such as an unmarried young woman). In “The Hidden Treasures of the Art of Physick” is written:

“If the Sick be a married Woman let her have carnal Conjunction with her Husband as soon as ever the Fit is over. If that cannot be had, that is, if she be a Maid or Widow, let a Mid-wife tickle the Neck of the Womb with her finger anointed with Oyl of Musk, Cloves or the like, that so the offensive Sperm may be avoided”.

This approach to distressed young unmarried women, seen as due to sexual frustration, and “cured” by tickling of the uterus, was thus thought to elegantly deal with both the relief of the sexual frustration (and secondary “cure” of the various symptoms), while also preventing pregnancy. Astonishingly, this approach remained until well into the 20th century, providing the basis for much of Freud’s theories of “Hysteria”, a word derived from the Greek word for uterus hystera (ὑστέρα).

SHAKESPEARE AND TNE OVER-BEARING FATHER

Plays of the era suggested that “greensickness” was overdiagnosed and that over-protective fathers and doctors were often to blame, respectively due to fear of sexual development of their daughters, and by regarding puberty as a clinical condition.

In “The Two Noble Kinsmen” Shakespeare however shows the doctor to demonstrate common sense, in contrast to the father of the sexually frustrated daughter. The doctor’s prescription is to satisfy her body by giving her what she desires, namely a previous suitor to “lie with her”. The father’s concerns about her potential loss of chastity is answered by the doctor:

“That’s but a niceness.

Nev’r cast your child away for honesty.

Cure her first this way: then if she will be honest,

She has the path before her”

In other words, Shakespeare is condemning fathers as fools who would risk a daughter’s life rather than lose her virginity. This approach by Shakespeare came late in his writing career.

In a recent book by Deanne Williams, entitled The Performance of Girlhood, reviewed by Potter, she deals with the issue of how girlhood was represented in early modern theatre (16-17C). She particularly addresses the Issue of father-daughter relationships in Shakespeare’s plays and how this changes over time, She notes that while in earlier plays daughters are often portrayed as erratic and immature, in later plays such as Pericles, Tempest and Winter’s Tale, daughters such as Hermione in Winter’s Tale are seen to be educated and developing independence.

A further fascinating observation regarding father-daughter relationships is that Shakespeare’s successful heroines who survive perilous circumstances, such as Rosalind (As You Like It), Portia (Merchant of Venice), Beatrice, and Helena – do so because their fathers are either dead or absent. In contrast, those who are having hard times have fathers who adhere to outdated concepts of daughterly conduct, failing to recognize girlhood as a distinct stage of development. So once again, Shakespeare comes to believe that over-bearing fathers are responsible for stifling their daughters’ development and independence, whether it be in fear of their daughters’ sexuality (as discussed re Greensickness), or in their overall success in surviving adversity and achieving adult independence and resilience. These are indeed profound observations of the human condition, no less relevant in today’s world.

CONCLUSION

Representations of adolescence in Shakesepeare’s plays is thus a fascinating subject, with some critics arguing that he ignores the adolescent period, while more recent scholarship speaks to a far more nuanced and complex approach.

Puberty and most of its elements were thus recognized in Shakespeare’s time and indeed as early as the ancient Greeks. Concepts included recognition of the developmental stages of puberty, with some errors, humoral explanations of physiology, which are in some ways remarkably close to hormonal explanations, specifics of male and female manifestations in behaviour as well as physically, some distortions of pathophysiology, but again some remarkably astute observations, with cures that persisted till early 20C. Roles of fathers and mothers. Lots about transgender!! A lot to learn.

DISCUSSION

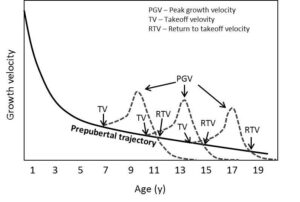

Ze’ev Hochberg: In the depiction of puberty in the literature, you would think that at the time of Shakespeare and in today’s literature puberty would be described similarly. The depiction of puberty at that time and today is very different. As you said, in Shakespeare’s time the emphasis was on the heat, on sexual activity and on temptation of the adolescent. If you read modern literature, adolescence is mostly described as an age of confusion. I would think that it has to do with the age of puberty then and now. In Shakespeare’s time, puberty was much later than it is today, probably some four years later. What’s happening today is that physical puberty comes much earlier, but the mental component of adolescence comes later, so that there is a mismatch with the readiness of the child. This is the basis for the confusion among today’s adolescents, whereas in Shakespeare’s time there was probably a greater synchrony between physical puberty and mental puberty, so that his description is more accurate with respect to the essence of adolescence, an age of heat and temptations.

Werther: You are right. It is interesting though from what I have read, in the plays, they still talk about menarche occurring at somewhere around age 13, which is not that different from today, but of course you are saying that is not historically correct.

Alan Rogol: I wanted to make two comments. The first one, from what Ze’ev said: Actually, the two times seven, fourteen, at that time was probably about right. It didn’t come till later in the Industrial Revolution that it went up to seventeen, and then came back down. But one other thing that we used to say as paediatricians and endocrinologists that you went to a child, to an adolescent, to a young adult. But some of the psychology these days is now you had emerging adulthood which comes after adolescence, but before being able to be on your own. I think that is exactly the dichotomy that Ze’ev brought up.

There is one other thing that came up: When they are ready for fertility, several of your references noted that they hadn’t reached their full muscularity and full body composition for boys, which is often early in the third decade. So I think he actually had some pretty good observations.

Werther: Yes, one of the references I gave was that boys should not have sex too early because “their seed is thin”, reflecting what you just said.