Ze’ev Hochberg, MD, PhD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

Melvin Konner, MD, PhD, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Editor: Ivo Arnhold; Reviewer: Alan D Rogol

Hochberg and Konner: In this Conversation, we suggest that the duration of human maturation has been underestimated; an additional 4-6-year pre-adult period, which overlaps with what psychologists call “emerging adulthood”, should be included in models of human maturation. As we define it, the transition between adolescence and emerging adulthood occurs when the decelerating pubertal height velocity equals the pubertal takeoff velocity (to be detailed later).

Hochberg: When using physical, physiological, intellectual, social, emotional, and behavioral measures, at the end of adolescence, an individual cannot be considered an adult. When adolescents in developed societies mature and achieve adult body size, their behavior often remains immature. Specialists in adolescent medicine have recognized this incongruity, and have redefined adolescence to include young adults up to age 24 years, of whom many have not yet assumed lifelong adult roles. Reproduction in contemporary forager societies also begins several years after adolescence and post-adolescent individuals are often limited in their gathering and/or hunting skills. In a comparative mammalian context, primates produce few offspring; the reproductive strategy of humans includes an even slower growth rate than that of nonhuman primates of comparable size, but human growth may be even more prolonged than is generally realized.

Konner: Arnett proposed emerging adulthood as a phase of life between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood, with distinctive demographic, social, and subjective psychological features1,2. This life-history stage, by his definition, applies to individuals aged between 18 and 25 years, the period during which they become more economically independent by training and/or education. Previously, the psychodynamic theorist Erik Erikson identified a stage that he called a prolonged adolescence or psychosocial moratorium in young people in developed societies 3,4. Much more recently, Hopwood and colleagues explored genetic and environmental influences on personality development during the transition to adulthood in a sample of same-sex monozygotic and dizygotic twins assessed in late adolescence (~ age 17), emerging adulthood (~24y), and young adulthood (~29) 5. This transition also involved changes in personality traits in the direction of greater maturity and increased stability. They found that trait changes were more profound in the first relative to the second half of the transition to adulthood; that traits tend to become more stable during the second half of this transition; and that both genetic and non-shared environmental factors accounted for personality changes. Interestingly, the United Nations has defined emerging adulthood during the period from 15 – 24 years of age, as a period of vulnerability worldwide and has made it a priority for multiple interventions.

Defining the Transition from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood

Hochberg: Using an evolutionary approach to understand emerging adulthood, I argue that it is not just a sociological transition period but also a true life-history phase in biological terms. Life-history theory is a powerful tool for understanding child growth, maturation, and development from an evolutionary perspective. It provides evidence that emerging adulthood exists in some other mammals, which implies genetic evolution, and we discuss emerging adulthood in foraging as well as developed societies, which implies the occurrence of adaptive plasticity and cultural influences. I propose that genetic and cultural evolution have interacted to produce the emerging adulthood stage in human life history.

Determining the exact time at which transitions between life-history stages happen is challenging. Saltation (growth spurts), stasis and transitions occur during human growth, and stages have a central place in evolutionary life-history theory, but the turning points are theoretical constructions in which some aspects of a transition are highlighted6.

Puberty produces an endocrine transformation with striking somatic and behavioral changes, including in the domains of body image, sex identity, aggression, and impulsivity. To define a maturational stage between adolescence and adulthood, we need first to define the end of adolescence. During this transition, growth velocity decelerates, hormone levels increase, aggression becomes less overt, and learning and maturation ease hormonal impact.

Using maturational measures avoids the pitfalls of defining emerging adulthood according to chronological age. Tanner stage V recognizes the conclusion of puberty in boys. I define the transition between adolescence and emerging adulthood as occurring when growth returns to its prepubertal trajectory, and the boy or girl is at Tanner stage IV. The boys at this stage have a testicular volume between 12 and 20 ml. Body composition continues to change during emerging adulthood, in terms of relative fat mass (females exhibit less trunk fat than males), lean body mass, and bone mineral content and mineral density increase.

Konner: But the most important maturational changes after adolescence are in the brain. Brain size may be a pacemaker in mammalian life history; the length of the brain’s developmental trajectory was until recently underestimated. It is now clear that brain development does not stop with the completion of puberty, when adult brain size is attained. Brain maturation continues beyond adolescence, extending until around age 25 years, and this recently discovered prolongation provides critical support for emerging adulthood as a post-adolescent maturational stage. The cortical architectural units or minicolumns in the prefrontal cortex of humans are wider than those of the great apes, with an increase after puberty in humans, but not in chimpanzees. In chimpanzees, but not in humans, myelination becomes complete at about the time of sexual maturity. Interestingly, human brain regions with protracted development are the same that have undergone the greatest degree of volumetric enlargement in primate evolution.

Hochberg: In a large-scale longitudinal pediatric neuroimaging study, it was reported that brain maturation continues after adolescence: the post-adolescent increases in white matter are linear and the changes in the cortical gray matter are non-linear. Cortical white matter in particular continues to increase into the mid-twenties, which is likely related to the efficiency and speed of cortical connectivity7,8. In another study, Sowell and her colleagues spatially and temporally mapped brain maturation in North American adolescents (age 12-16) and young adults (age 23-30) using a whole-brain structural magnetic resonance images9. They found that the pattern of brain maturation during these years was distinct from earlier development and was localized to large regions of the dorsal, medial, and orbital frontal cortex and lenticular nuclei. They also reported that relatively little change occurred at other brain locations. They concluded that cognitive functions improve throughout adolescence, and this improvement is associated with simultaneous post-adolescent reductions in gray matter density (as white matter increases) in frontal and striatal regions. As a growing body of knowledge shows that criminal behavior has a neurobiological basis, such brain changes may mitigate the guilt of adolescent delinquents who have not yet gone through them.

Konner: Investigation of white matter maturation during adolescence, using diffusion tensor imaging, reported that sex hormones influence white matter development and maturation and that white matter connectivity and the executive control of behavior is still immature in adolescence. Thus, functional connectivity continues to change during and after adolescence, and these developmental differences in functional connectivity patterns were associated with higher cognitive or emotional functions and basic visual and sensorimotor functions.

Other studies support this contention10 11; brain development and maturation continue in emerging adulthood, and the idea that brain maturation is finalized during adolescence is no longer tenable.

Hochberg: Psychologically, emerging adulthood is a stage when an individual’s cognitive abilities increase to reach their peak in their third decade and possibly beyond. The critical abilities are those that enable the learning of new things, that is, working memory and fluid intelligence; these peak in the mid-20s.

Emerging adulthood is also a social stage: it is a period of learning intimacy and mutual support, intensification of pre-existing friendships, family-oriented socialization, political awareness, developing new relationships, and the attainment of biosocial skills that are needed for successful mating and reproduction. It is a stage of understanding self-concepts and ideal concepts, emphasized interpersonal reactivity and obligation, self-expressiveness, and contempt towards particular ideologies. The attainment of these cognitive, emotional, and social abilities is the result of a complex interplay of maturation and interaction with the environment, and, at least in the earlier years of emerging adulthood, they are in part the phenotypic expression of brain maturation.

Konner: There is also evidence that brain growth continues into the third decade in some individuals, especially boys. In these individuals, hypothalamic maturation, puberty, and the resultant hormonal surges are dissociated from and even precede development and maturity of frontal cortex.

Hochberg: Emerging adulthood begins as a physiological, but most importantly a neural transformation in which behavioral and social functions interact, with consequences for impulse control in domains that have put the individual at risk during puberty. We argue that this life-history phase has unfolded throughout hominin evolution.

Growth-related Definition of the Transition to Emerging Adulthood

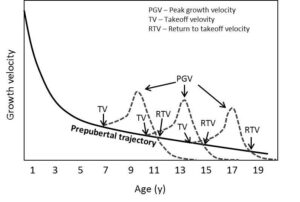

Hochberg: To define the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood, I use the age at which growth velocity returns to the prepubertal trajectory (Figure). The adolescent growth spurt can be identified from the growth velocity curve, and its takeoff is signaled when the rate of growth changes from deceleration to acceleration at the end of the juvenile stage. This inflection point marks the beginning of the adolescent growth spurt. The point at which the curvilinear growth velocity spurt returns to the pre-takeoff (decelerating) trajectory defines for us the end of adolescence and the beginning of emerging adulthood.

Figure legend: Schematic representation of the age-dependent pubertal take-off velocity and the return to prepubertal trajectory, showing early, average, and late maturers. The age-dependent decline in peak height velocity is a function of the decelerating prepubertal trajectoty. PGV – peak growth velocity, TV – takeoff velocity, RTV – return to prepubertal growth velocity curve.

In an allometric analysis of 21 species of anthropoid (human-like) primates, the age at return to takeoff velocity and the adult body mass positively correlated. The age at return to takeoff velocity in both females and males occurs later in human beings than other primates because of the lateness of our growth spurt when body mass is considered. Overall, the growth spurt in most primates is minimal, and little is known about the relationship between the age at return to prepubertal growth velocity and the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics at puberty. Takeoff velocity occurs early in gorillas, and despite their greater body mass, female gorillas become sexually mature at a younger age than female chimpanzees. Similar to humans, vervet (Cercopithecus aethiops) and rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) show a relatively late return to prepubertal growth velocity. Interestingly, this positive correlation between the age at return to prepubertal growth velocity curve and body mass also exists in six pre-industrial societies described in Walker’s Database for Indigenous Cultural Evolution (http://dice.missouri.edu/)

The Evolutionary Context of Emerging Adulthood

I: Evolutionary Life-History Theory

Hochberg: Life history has been defined as the allocation of an organism’s energy towards growth, maintenance, reproduction, raising offspring to independence. Evolutionary life-history theory attempts to explain and predict tradeoffs that optimize energy expenditure, reproductive advantage, and risk. Central to the concept of sexual selection is the attainment and optimization of reproductive competence, and the key traits for selection are growth, maturation, and the age at transition to adulthood when an individual is independent and capable of reproduction12.

Konner: Human beings and the great apes share similar developmental traits, including some aspects of emerging adulthood. Low reproductive success among young females has been reported to be a general primate phenomenon. Non-human great apes have a 2-year period of post-menarcheal infertility, extended in many human foragers to 3 years.

Male preference for fully developed adult females has been described in 15 primate species. Jane Goodall reported that following menarche, which usually occurs at age 10 years, the female chimpanzee averages 19 cycles before she becomes pregnant for the first time at age 12 years. She will have about 60% of her lifetime sexual encounters during this post-menarcheal period. Chimpanzees and bonobos live in multi-male and multi-female groups and mate more often than needed to conceive. Accordingly, primatologists have suggested that adolescent sterility or subfertility is a period in which sexual and social skills are practiced without taking responsibility for the care of a newborn.

In their emerging adulthood, female vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) display a high degree of interest in young infants and will touch, cuddle, carry, and groom infants whenever they can. This play-mothering by young females may be an opportunity to not only practice motor skills, but also as opportunities to practice their expected maternal role in society.

The sexual encounters of young females with males, who are unaware of their low reproductive potential, are also used as a means of barter for other commodities in the biological market, such as food. Fecundity in males depends on the male’s age, size, and experience. Similar to humans, where reproductive success is in-line with hunting ability, reproductive success among Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) is much lower in young males than fully adult males. In male chimpanzees, pre-fertility copulation is common.

While it is challenging to ascertain the life-history stages of ancient hominids, the timing of their dental maturation from the fossil record has shed some light on their life-history stages. Australopithecines are anatomical intermediates between apes and human beings and chimpanzees and bonobos are often regarded as living species that can to some extent represent the australopithecines. Based on detailed reconstructions of dental specimens from the fossil record, the life-history stages of the australopithecines resemble those of wild chimpanzees, and not those of modern human beings. Homo species (the last 2.2-million years) mature more slowly and the attainment of certain maturational milestones, such as the onset of puberty, adolescence, and the assumption of reproduction, probably occurred later, in parallel with their increasing longevity, body mass, and height.

A life-history tradeoff is a fitness cost that occurs when a beneficial change in one trait is linked to a detrimental change in another trait. The Charnov model of mammalian life-history evolution derives the flow of life-history consequences from the adult mortality rate13:

Adult mortality Age at maturity Adult weight Fecundity Juvenile mortality

According to this model, any factor or influence that decreases adult mortality, such as large adult body mass, sociality, or living in a low-predation environment, would favor delayed maturation. A large body size is potentially protective and a mortality deterrent for mammals. Reproductive value (RV), a measure combining the cost of growth and the remaining length of reproductive life, increases with body mass while growth rates decline; the optimal age to stop investing in growth is when the expected RV starts to decline. Body mass and age are mathematically coupled because body weight increases during growth, and growth stops at a certain age when body weight is optimal. Accordingly, juvenile survival becomes important when maturation is delayed. Furthermore, increasing juvenile survival and extending the adolescent stage in an individual’s life history increases that individual’s RV. Hence, including emerging adulthood in the life-history strategy of a species to increase juvenile survival of that species is highly favored. The offspring number of most species with a large body size is small, and juvenile mortality decreases when reproduction is late.

Several tradeoffs could underlie the prolonged period of emerging adulthood in the life-history strategy of human beings: a) reproducing at an earlier or later age; b) reproducing at a young age or continuing to grow and develop; c) being a fully adult parent with a large parental investment in each offspring of a small family or a younger parent with a smaller parental investment in each offspring of large family. In facultative tradeoffs, individuals adjust their energy budgets and risk to environmental conditions within a genetically specified range or norm of reaction. The Charnov model predicts that a long life span will be associated with slower maturation, repeated reproduction, a single offspring at a time, and long parental care.

Slow rates of growth, reproduction, and aging among primates reflect their low total energy expenditure. Emerging adulthood is part of the historical lengthening of both ends of the pre-reproductive life span of human females (early puberty and late reproduction) in response to improved nutrition and decreased mortality due to infectious disease 14,15. Microevolutionary tradeoffs that might underlie an extended emerging adulthood stage of life history include the allocation of energy to growth or reproduction, and the energy investment in courtship or parenting.

For higher primates, performing the sexual act requires good cognitive ability and specific sexual behaviors. During human evolution, the acquisition of certain abilities resulted in the lengthening of maturation and development.

When comparing humans to our ape relatives, the Charnov model of mammalian life-history evolution helps explain prolonged growth and maturation, including the period of emerging adulthood. Using Charnov’s model, we also suggest that emerging adulthood is the foundation of the high productivity of human beings: the metabolic potential of human beings exceeds the metabolic requirements of survival and this excess is first used to support growth and brain development before being allocated to reproduction.

Hochberg: Despite the fact that the human pre-adult life-history is longer than that of the chimpanzee, and that human infants are larger than chimpanzee infants at birth, hunter-gatherer women characteristically have higher fertility than chimpanzee females. Anatomically modern human parents care for their offspring throughout their offspring’s adolescence and emerging adulthood, and this extended period of care is longer than that of other primates.

Konner: The unique evolutionary path to the genus Homo was shaped by an increasing reliance on calorie-dense, large-package, skill-intensive food resources, and this increased reliance entailed co-evolutionary selective processes, “which, in turn, operated to produce the extreme intelligence, long developmental period, three-generational system of resource flows, and exceptionally long adult life characteristic of our species” 16. Kaplan and Robson emphasized the role of human males in provisioning meat to their family and band members. They also highlighted the contributions of grandmothers and other family and band members to provisioning and childcare, reflecting the importance of their contribution to survival and success in emerging adulthood.

Although the average menarcheal age of the gorilla, the bonobo, and the chimpanzee is 7-8, 9, and 11 years, respectively, their age at first birth is 10-12, 13-15, and 14-15 years, respectively. Despite their rapid development compared with humans, the great apes have a distinct period of post-menarcheal life with no fecundity. In parallel with other great apes, the menarcheal age of human forager populations ranges from 13-19 years, and their first birth occurs about four years later when they are between 17-23 years of age. In contrast to the great apes, the primiparous women of forager populations were supported and provisioned by mature adults: grandmothers, who were usually post-reproductive; their husbands, who were typically several years older and have often passed through the emerging adulthood stage of their life history before marriage; other adults.

Despite similarities among primates, the prolongation of dependency during emerging adulthood is unique to human life history, and is part of the evolutionary success of Homo sapiens.

II. Development of the Human Reproductive Strategy

Hochberg: Across forager societies, there is a consistent 3-4-year period between menarche and the birth of the first child; adult reproductive behaviors are learned during this period of emerging adulthood. The evolution of human development culminated in environment-dependent and late reproductive maturation. According to life-history theory, the reduction in juvenile and adult mortality postponed reproduction and necessitated substantial parental investment in each offspring.

Despite cross-cultural variations in the age of initiation of sexual activity and the age at marriage, the period of emerging adulthood in all cultures involves readiness for mating. Strong emotions often accompany early sexual activity; during adolescence, the frequency of depressive episodes is temporarily increased in boys and girls, and the frequency of these episodes is higher in girls than in boys. Sex hormones are responsible for intensifying the behavioral and psychological changes that occur during adolescence, but in emerging adulthood and into adulthood, average rates of depression, anxiety, and risk-taking decline.

Interestingly, serum testosterone levels continue to rise after puberty and peak in the third decade in men. This age-dependent increase in serum testosterone levels does not occur in chimpanzees: serum testosterone levels are higher in adolescent chimpanzees (age 7-10) than in adults (age >11 y). Male and female sex drive are intensified (and/or enabled) by the activation effects of the sex steroids as part of a switching mechanism that re-allocates resources from growth to reproductive activity during emerging adulthood.

Konner: The “fight or flight” response to perceived threat influences life-history tradeoffs during development. As part of their readiness for mating, the bullying behavior of adolescent males diminishes at transition to emerging adulthood. This could be due to adolescent’s learning more subtle ways of outcompeting competitors. While relational aggression becomes more subtle and sophisticated, the underlying motive for dominance and resource control is still there.

Hochberg: Bullying is a complex social problem that can have serious negative consequences for both bullies and victims. The negative effects of bullying are well documented, not only in terms of the psychological harm that is inflicted upon victims, but also in terms of the maladaptive outcomes for children who engage in bullying. As moral emotions mature toward emerging adulthood, i.e., guilt and shame versus indifference and pride, so does bullying diminish. Whereas it is not yet clear whether or not moral disengagement strategies change with age or are equally available to individuals across the age range, it seems that some strategies for

moral disengagement subside when early adult social and cognitive development emerge.

III: Adolescence and Emerging adulthood among the !Kung and Other Foragers

(! Signifies a click in the Bushmen JU language)

Hochberg: Contemporary forager societies are modern representatives of pre-agricultural forager societies. The mean age difference between men and women at the time of their first marriage in 191 national populations and traditional societies is 3.5 years. The acquisition of subsistence skills depends on both physical development and social access.

Konner: The !Kung are contemporary foraging people of the Kalahari Desert, whose demography and life history have been extensively studied. Traditionally, their average age of menarche was 16.6 years (range 16-18), and about 50% of these young women are married before menarche to men who were on average ten years older. The results of a retrospective study of !Kung women who were 45 years or older estimated that their age at first childbirth was 19 years (range 17-22). This 3-year period between the age of menarche and the age at first birth is probably due to subfertile ovarian cycling. Although their husband’s sexual advances were supposed to be delayed until menarche, women reported that this period was often stressful. This 3-year period is important for a newly married !Kung woman for at least two interwoven reasons.

First, she gradually learns to adopt adult roles and acquire adult sexuality without having to deal with the consequences of pregnancy and feeding a family. Second, a young married !Kung woman usually lives near her mother, even after the first birth, because she is dependent on her mother, father, and extended family before moving to her husband’s village-camp after a second child.

Although !Kung women usually become socially responsible mothers with two or more children by their mid-20s, these mothers are typically still being provisioned by their families. Psychosocial development during emerging adulthood is substantially longer in boys than in girls, and the transition from adolescence to adulthood is gradual. !Kung boys learn hunting and other subsistence skills and are permitted to accompany adult men on hunting trips when they are in their mid-teens. However, the husband’s obligation to provision his family with meat is also aided by relatives during the period of emerging adulthood.

To what extent do the !Kung represent other contemporary hunter-gatherer societies? The acquisition of subsistence skills is a very long process among the closely related San people of the Okavongo Delta, Botswana. Mongongo nuts are a staple food for these people and the !Kung, and acquiring the skill to crack these nuts is age-specific, because nut-cracking skill and arm strength is less important than age. Plotted against age, the ability follows an inverted U-shaped function across the lifespan, and this time-dependent function is a good example of the adaptive evolutionary value of emerging adulthood beyond adolescence. Success at nut-cracking is minimal until the late teens and then this skill improves until midlife before declining.

The Hiwi Indians of Venezuela and the Aché Indians of Paraguay are traditional hunter-gatherer groups whose hunting and subsistence skills gradually increase throughout young adulthood. Although Aché girls collect insect larvae for subsistence, children of the two tribes under age 10 years do almost no foraging and especially no hunting until their teenage years. Specifically, the skill of gathering honey and palm fiber of Aché boys and Hiwi girls progressively increases to levels that are about half of their peak adult values in adolescence. The age at which the hunting skills of Hiwi and Aché men are at their best is the late thirties, and the age at which Hiwi and Aché men and women reach their peak gathering skills for honey and palm fiber occurs when they are even older.

Research on the Tsimane foragers of Bolivian Amazonia, are also relevant to explaining the purpose of the long pre-adult life history of modern humans. Based on hunting returns and the results of specific skill tests, the peak performance of hunters is only reached several years after the completion of a long childhood and adolescence; hunters must first learn to recognize the sounds, the smells, the tracks, and the feces of critical prey species, and then learn to hunt by sightings, pursuits, and attempted kills. The hunting performance and ability of Tsimane foragers is another example of a skill whose acquisition depends on the individual’s age and not the individual’s strength.

Blurton Jones and Marlowe confirmed increases in skill and performance with age in the Hadza, hunter-gatherers of northern Tanzania. For example, accuracy when shooting with a bow and arrow among men Hadza people increases with age and reaches its peak at age 25. One cannot assume that the age-dependent increase in performance and ability is entirely due to learning and/or practice; the increase may also be due to increases in an individual’s size and strength.

The importance of size and strength is confirmed by a study of spearfishing and shell fishing efficiency among the Meriam, who live on the Mer and Dauer islands in the eastern Torres Strait. For fishing and spearfishing, which are cognitively difficult, Bird and Bird found no significant amount of variability in return rates because experiential factors correlated with age. However, for shellfish collecting, which is relatively easy to learn, they found strong age-related effects on efficiency.

Thus, the evidence from foraging societies and the conditions in the environment to which humans became adapted during our evolution show that neither reproductive behaviors (i.e. parenting and the ability to manage the relationship with a spouse) nor subsistence skills are mastered by the end of adolescence.

From the evidence collected from various foraging societies in different global locations, performance proficiency of subsistence skills of individuals increases with age and only peaks when they transit from emerging adulthood into adulthood in their twenties or later. These findings confirm that the period of emerging adulthood is marked by age-dependent maturation, ongoing brain development, strength accrual, and learning, and is a key adaptation for human survival and reproduction.

Secular Trends in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Hochberg: Menarcheal age has declined in the U.S. and Europe for over a century. It has declined by four years over the past 150 years, and the age at peak height velocity in the pubertal growth spurt has decreased by four months per decade. An evolutionary approach to this secular trend challenges the concept that early adolescence is a disease process, and suggests that contemporary reproductive and life-history strategies are reflected in the substantial increase in the presentation of females with early-onset puberty.

Secular trends indicate that the duration of pre-adolescent growth and development has shortened over the past two centuries, and a decoupling between pubertal/hormonal maturation and brain maturation has occurred in adolescents in developed societies. While the mental development of adolescents and emerging adults in developed societies is as slow or slower than that of those in predeveloped societies, the onset of puberty in the developed societies now occurs at a younger age than that in the predeveloped societies. Many people in advanced developed states have increasingly recognized the need for prolonged period of education and support beyond adolescence.

Part of the misconception that early adolescence is a pathological condition is related to the assumption that the transition from adolescence to adulthood is direct. The subfertility of emerging adulthood can be explained by the period between the age at menarche, which is currently 12.5 years in Europe, and the modeled optimal age at first birth of 18 years. Indeed, puberty is followed by subfertility in adolescence and emerging adulthood due to a high proportion of non-ovulatory cycles. Currently, there are no appropriate data for a secular trend in the age at first consistent ovulation.

Despite liberal morals and adolescent sexual activity, early childbearing was uncommon in pre-agricultural societies. In a non-developed traditional society, a girl who begins to menstruate at age 15 years can take her place in that society at age 19 years as a young mother after a 4-year period of emerging adulthood and be supported by the institutions of marriage and an extended family.

In developed societies, the period of emerging adulthood of a girl who begins to menstruate at 12.5 years is prolonged. This prolongation coincides with slow development of the prefrontal cortex and other brain structures and late myelination until at least age 25 years. Gluckman and Hanson have emphasized the mismatch between early-onset of puberty and late mental development in contemporary developed societies, and it is the later part in this period of mismatch that we define as emerging adulthood, a time when young adults are still immature in their judgment and less capable of performing adult tasks17.

Summary and Conclusions

Hochberg and Konner: The idea that one of the outcomes of human evolution is a very prolonged period of adolescent growth and delayed maturity is old, and is consistent with life-history theory, comparative primatology, and the hominid fossil record. We suggest that emerging adulthood is a life-history stage that is part of the foundation the high productivity of human beings: the metabolic potential of human beings exceeds the metabolic requirements of survival and this excess is first used to support growth and brain development before being allocated to reproduction.

We contend that the duration of maturation in human beings has been underestimated, and that an additional 4-6-year pre-adult period, which (following Arnett and other psychologists) we call emerging adulthood, is not restricted to modern societies and should be included in human life history. Recent evidence from brain imaging studies has shown that brain development continues throughout emerging adulthood; development of the neocortical association areas, notably the frontal lobes, extends into the mid-twenties, and is still incomplete long after the end of puberty and linear body growth.

There is now abundant evidence that the frequency of behavioral disturbances of adolescence, such as unplanned sexual activity, risk-taking, impulsivity, depression, and delinquency, declines after adolescence despite persistent high levels of gonadal hormones. The most likely explanation for the transient nature of these behavioral disturbances of adolescence is continuing myelination of the frontal cortex and other brain regions that are involved in the management of impulses and emotions.

Adolescence is often delayed in foraging societies. Since the women in these societies have late menarche and are subsequently subfertile, the age of these young women at the time of first birth is 19 years and their husbands are generally several years older. These young parents are strongly supported by older family members, who supply needed food and advice. The mastering of subsistence skills takes many years and an individual generally becomes most proficient in these skills in their fourth decade. These realities highlight the adaptive advantages of a post-adolescent or an emerging adulthood phase of human maturation, which requires substantial brain maturation and learning.

In the developing world where traditional structural support systems have collapsed, parents are often not able to provide the experience of emerging adulthood to their children, leading the United Nations to identify youth, defined as 15-24 years of age, as a demographic group at risk and a special target for intervention.

The period of emerging adulthood has an evolutionary context and a prolonged maturational underpinning, and we present evidence that supports the idea that emerging adults require protection because they are still both learning and maturing.

References

1. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American psychologist. 2000;55(5):469.

2. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood (s). Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy. 2010:255-275.

3. Erikson E. H.(1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

4. Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950.

5. Hopwood CJ, Donnellan MB, Blonigen DM, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on personality trait stability and growth during the transition to adulthood: a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(3):545.

6. Hochberg Z. Evo-devo of child growth II: human life history and transition between its phases. Eur J Endocrinol. Feb 2009;160(2):135-141.

7. Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2(10):861-863.

8. Giedd JN, Raznahan A, Alexander-Bloch A, Schmitt E, Gogtay N, Rapoport JL. Child Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health Longitudinal Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Human Brain Development. Neuropsychopharmacology. Jan 2015;40(1):43-49.

9. Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2(10):859-861.

10. Kelly AC, Di Martino A, Uddin LQ, et al. Development of anterior cingulate functional connectivity from late childhood to early adulthood. Cerebral cortex. 2009;19(3):640-657.

11. Lebel C, Beaulieu C. Longitudinal development of human brain wiring continues from childhood into adulthood. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(30):10937-10947.

12. Hochberg Z. Evo Devo of Child Growth: Treatize on Child Growth and Human Evolution New York: Wiley; 2012.

13. Charnov E. Life History Invariants: Some Explorations of Symmetry in Evolutionary Ecology, 1993. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 1993.

14. Eaton SB, Pike MC, Short RV, et al. Women’s reproductive cancers in evolutionary context. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1994:353-367.

15. Worthman CM. Evolutionary perspectives on the onset of puberty. Evolutionary medicine. 1999:135-163.

16. Kaplan HS, Robson AJ. The emergence of humans: the coevolution of intelligence and longevity with intergenerational transfers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jul 23 2002;99(15):10221-10226.

17. Cauffman E, Steinberg L. (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behav Sci Law. 2000;18(6):741-760.